Story by Steve Frankham

Photos by Ram Raj Dhakal and Steve Frankham

Sitting behind Nana on his bike, we bump slowly down a dirt track through the morning mist. We’re heading through the outskirts of Thakurdwara, a small town in Nepal’s lowland Terai region. Making our way around piles of stones and potholes in the road, we pass lush fields of yellow mustard, banana palms, and wide-buttressed silk cotton trees. Many of the houses, built with traditional mud walls, have ‘living’ grass roofs, with plump pumpkins growing out of them. Here you can literally eat your roof!

People of the forest

As we pass many of these simple, beautiful homes, colourfully dressed men and women collect grass and fodder for goats and pigs, people cook on open fires, and children, excited to see a foreigner on a bike, wave and shout enthusiastic ‘Namastes’ or ‘Hellos’ in greeting. Most of the people here are Tharu, an ethnic group who consider themselves ‘people of the forest’. The Tharu worship the forest and its creatures. Through sustainable agricultural practices and harvesting products from the surrounding jungle, they make a living in this remote part of Nepal’s far west.

A conservation success story

Thakurdwara is the main entrance to Nepal’s Bardia National Park (also spelled Bardiya). Bardia is Nepal’s most pristine national park in the Terai region, covering 968km², plus an extensive ‘buffer zone’. It is a wildlife success story, with the number of tigers in the park tripling in the last decade, and healthy populations of leopards, sloth bears, Indian rhinos, and wild elephants.

Conflict

But with this success has come wildlife conflict. As wildlife populations in the National Park expand, tigers, rhinos, elephants, and other jungle denizens seek new territories outside the park. Although wildlife rarely seeks conflict with people, living in such close quarters with such formidable creatures has risks and accidents can be fatal. During my time in the village, a twelve-year-old boy was killed by a leopard, and a marauding male elephant entered the village looking for food and destroyed a house. Local people receive some compensation from the government, but not enough. Also, how do you value a life? More help is needed, and that is why I am here and on the bike with Nana (this is his nickname – his full name is Ram Raj Dhakal).

Community Conservationists

Nana is a friendly, tall, rangy young man with an easy-going manner. He is an important part of a community conservation initiative, boasting more than 3000 members in the Bardia area. This initiative includes CBAPU, the Community Based Anti-Poaching Unit, and the RRT, the Rapid Response Team, a group that responds to wildlife conflict emergencies in the area.

The Khata Corridor

We’re heading out to a community forest in the Khata Corridor, a community conservation area that allows wildlife to migrate between Bardia and the Katarniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary in India. This corridor is an essential highway for wildlife that gives the animals the possibility of a long-term future. It allows wildlife populations to move and expand and prevents inbreeding in animal populations. Wildlife only thrives in Khata because the local community allows it to. With wildlife numbers increasing as habitats are restored, conflict must be reduced, both for the sake of wildlife and people. Many communities are beginning to feel like the benefits the park promised (in the form of eco-tourism, development, and jobs) have not materialized, while the risks they are exposed to have increased exponentially.

Bindrapur

We come to the end of the road. Across a small river, the great trees of the Bindrapur Community Forest rise up like a living wall. Getting off the bike, Nana leads me tentatively across a rather slippy log bridge and into the forest. We are here to check some of the camera traps Nana has set, to see what wildlife is currently inhabiting this area. The forest is also intensively used by the local community who come to collect fodder for their animals, plus fruit and plants from the forest. The people also fish in the rivers.

Unsung heroes

Walking into the forest, we’re met by the two guards who protect this community forest, Faguram Tharu and Tek Bahadur Tharu. Their job is to protect this area and to make sure it’s being used sustainably. Nana and the forest guards undertake this work for little or no financial reward and often have faced intense criticism from local communities for championing wildlife and conservation. They are unsung, unrecognized heroes. In conversation, it quickly becomes apparent that they feel ignored by major NGOs and government authorities, yet their work is essential to both the wildlife and communities living here.

A box of wonders

We walk down the track together, the forest pushing in on either side. My eyes scan the vegetation for signs of life, but everything is still. The jungle is sleeping. After a few minutes, we reach a fork in the track and the first camera trap. Remote camera traps are superb tools for monitoring wildlife populations. They can be left for weeks, unattended, capturing images of any creature that passes in front of them and triggers their infrared beam. Nana immediately gets to work, opening the camera’s protective case.

‘Let’s see what we have here!’ he says.

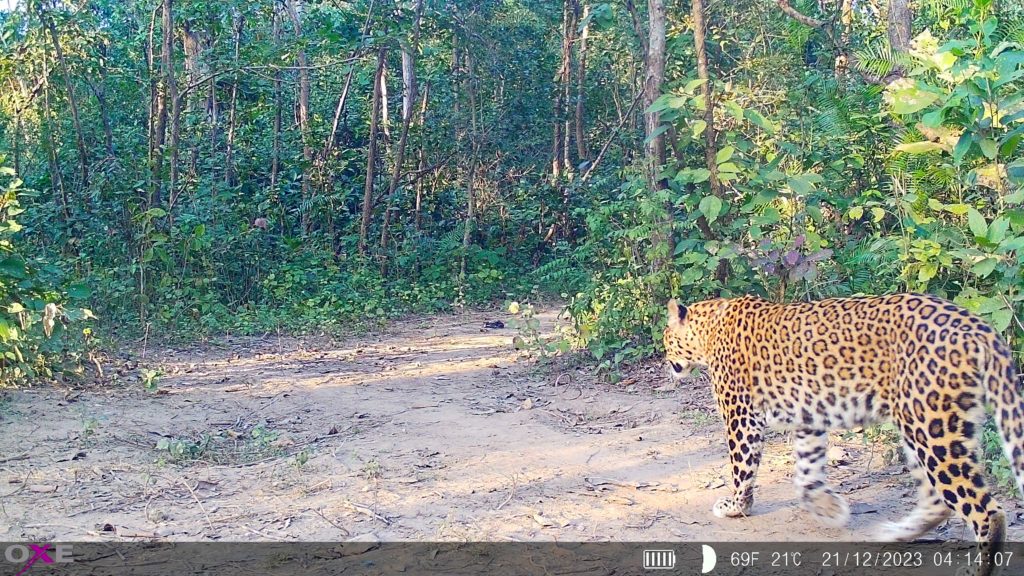

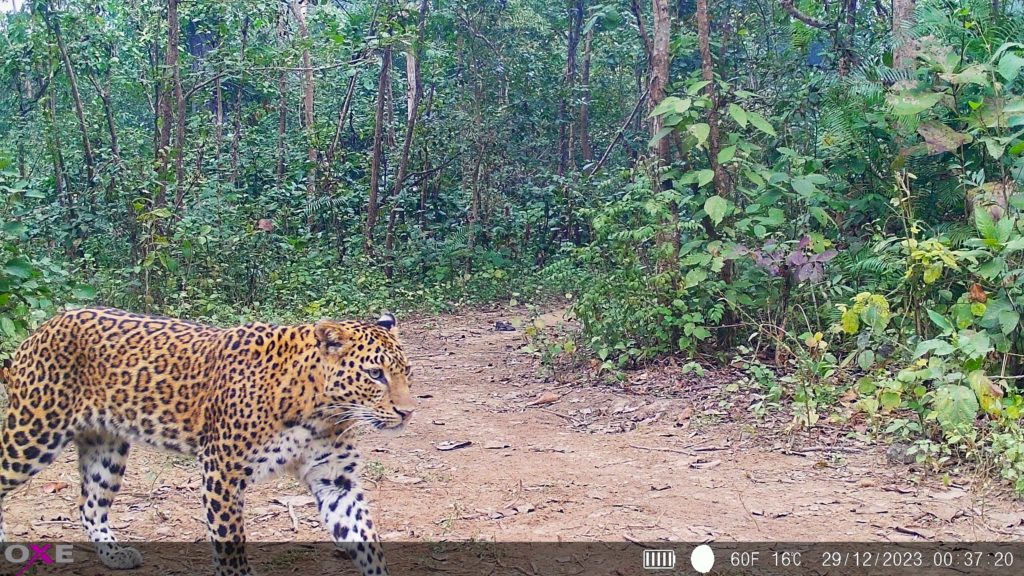

I’m full of anticipation as we flick through the photos captured on the camera. I’m not disappointed! Here, in this same spot where I’m standing, a leopard has passed this way, its pale eyes staring out of the image, hypnotizing me. There are civets, barking deer, and a leopard cat (prionailurus bengalensis), a rare smaller cat species, caught on its nighttime patrol.

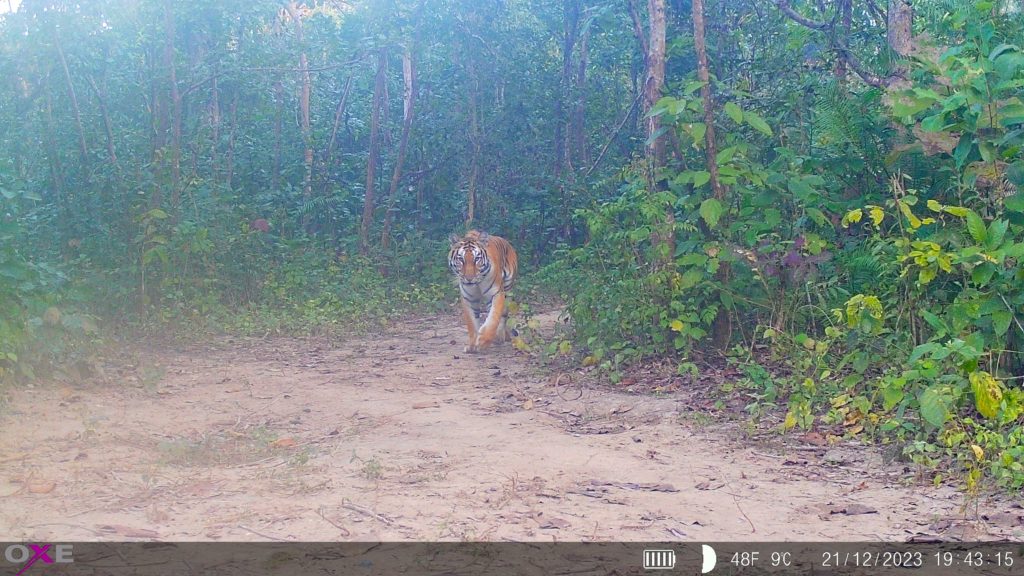

‘That’s the first time I’ve seen a leopard cat here!’ says Nana, clearly excited. Faguram and Tek also examine the image, impressed. And then, in the same place, I gasp as an image of a tiger presents itself, sauntering down the track towards the camera. This jungle might seem silent and still, but it’s overflowing with life – that is certain.

The living forest

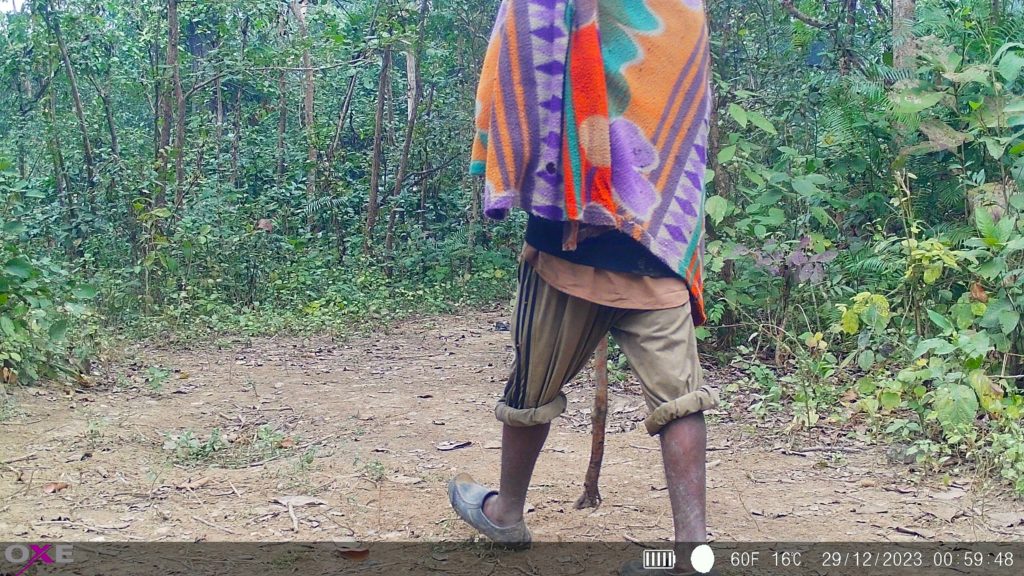

The presence of great carnivores like tigers and leopards is a sign of the forest’s health and its ability to support life. But there is more, in the form of people – people caught on camera collecting wood and fodder from the forest, as well as grazing livestock. One image shows the leopard and a person passing the same spot a mere twenty minutes apart. Many people are unaware that they are sharing this place with such mighty creatures, and this can be a problem.

A wake-up call

We move on down the track towards the second camera trap. On route, we pass a group of ladies cutting fodder in the forest with sickles, chatting lightly with one another. Nana starts a conversation in Nepali with the ladies, showing them images we have just seen on an old and battered laptop he is carrying. The ladies are clearly shocked and unnerved that they are sharing the community forest with not just leopards, but also an adult tiger. As we have this conversation, I muse on the fact that this same tiger might be resting only a few hundred meters away. It might be listening to our voices drifting through the trees!

After showing the photos, Nana explains to the ladies they must enter the forest in bigger groups and tells them to avoid the ‘dangerous hours’ of dawn and dusk when wildlife is most active, and what to do if they encounter one of these cats (do not run away!). He tells them to spread the word that the forest holds these potentially dangerous creatures. The ladies quickly hurry off, carrying their fodder, none too eager to meet the forest’s big stripey resident. It’s a wake-up call and an alert that could save lives.

The Treehouse

On the way to the next camera trap, we pass a treehouse that the community sometimes uses for tourists who want to spend a night or two in the jungle. It gets one or two visitors, but because of lack of publicity, it is an underused resource. These community forests see very little tourism, despite being awesome wildlife destinations in their own right. Almost all visitors head straight into the national park – which is spectacular, of course – but still, a more equitable vision of tourism that benefits the wider community needs to be found – and projects such as this treehouse could easily be part of the solution, generating much-needed income for poor families.

Where’s the help?

We continue to a few more camera traps. Each one tells the story of rich wildlife, living at close quarters with the community. One of the camera traps has recorded nothing. The SD card is broken, and this reveals another problem. The lack of resources, even for the basics. In addition, the computer is too old to play the videos the camera traps record. With no funding, Nana has to make do with this battered equipment.

‘Sometimes I have to buy batteries to keep the camera traps going myself’. He tells me. But this is a poor region, and sometimes he can’t afford it. Surely someone should be funding this essential work? He and the other volunteers put in so much time and energy to defend Bardia’s wildlife, but where is the help, appreciation, and resources that are needed for this essential fight?

A man of many talents

We’ve finished our check of the traps and we head back to town. On route Nana tells me about his work, rescuing pythons from people’s houses, running education groups with local children, and much, much, more. I’m impressed. Nana is a man of many talents, and I could easily see him teaching his community conservation skills to enthusiastic young students, both from Nepal and overseas.

Hemanta

The next day I met up with Hemanta Acharya, who runs the Community Based Anti-Poaching Unit, and the Rapid Response Team. Hemanta is in his mid-thirties, a serious and thoughtful man. His father was killed by a wild elephant – so he is as close to the debate on human-wildlife conflict as you can come. Nevertheless, he champions and defends wildlife in and around the park. But his message is the same. People need to benefit from this richness of the natural world, and not enough people are.

The northern border

Hemanta’s opinions were affirmed days later for me when I hiked to the park’s northern border. People in these communities had barely seen a tourist since before COVID, but animals, mainly barking deer in this case, eat most of their crops. Tourism has the potential to offset these losses, but currently, they have nothing. For the long-term sustainability of the park, more people need to benefit – and these people should not just be relatively well-off hotel owners and businessmen in the vicinity of Thakurdwara. More people, from a variety of communities and backgrounds around Bardia, need to have the opportunity to benefit from nature-based tourism. This process will obviously take time. But it needs to start now.

A call to action

Later that afternoon, Hemanta took me to a lodge, Tiger Track, that he is building with the support of Burhan Wilderness Camp. Tiger Track is envisioned as a place where locals and travellers can stay and learn about community conservation, and, of course, enjoy the wild beauty of Bardia. Before we part for the evening I hop on the back of Hemanta’s bike again, and we bump down the road once more towards the grassland in front of Dalla Community Forest. A couple weeks before I had some thrilling up close and personal encounters with tigers and a pair of rhinos in this same forest.

The sun is setting, the light is turning the swaying elephant grass gold, and men and women from the village are busy cutting the grass with sickles to thatch their houses. A few hundred meters behind, the forest overlooks the grassland. Wildlife and people living side by side. To keep it this way, we need to listen to the needs of the community and take real action.

How can you help?

The community conservation groups in Bardia featured in this article, CBAPU and the RRT are in desperate need of funding and support. Their work is essential for the long-term future of Bardia’s Wildlife.

Burhan Wilderness Camp, set on a beautiful island in the Khata Corridor, directly supports these community conservation initiatives in and around Bardia. For more information visit: Burhan Camps

Information regarding Tiger Track can be found at: www.tigertracknepal.com

For a fabulous homestay experience with an increadibly welcoming Tharu Family, you can’t beat Angna Ghar. This is run by Kaka and Kaki. Stay in a traditional Tharu longhouse with some of the most friendiest people you’ll ever meet! Call Kaka on +977 9812535063.

I can also personally lead and organise conservation-focused itineraries in Nepal and elsewhere. If your interested or have an questions, please contact: lacandongringo@yahoo.com

To check out an update of this article and community conservation work in Bardia, visit:

Interested in other conservation focused articles on this site? Check these out…

Land of the Lynx: a weekend of hope and despair in Doñana – The Lacandongringo

Making YOUR difference – small steps towards a greener world – The Lacandongringo

Saving the best for last: giant otters of Manu National Park – The Lacandongringo

Hope and devastation. A Story of Borneo’s Orangutans – The Lacandongringo

Your writing has a positive impact.

Here is a place that is straight out of Rudyard Kipling’s ‘Jungle Book’.

As magical as the stories we have read and a part of the world that needs protection.

It certainly is Jane…and it needs all the protection it can get!